Painting Thangkas

18 January, 2009, 01:12 am in "Nepal"

Thankgas are Tibetan/Nepali paintings on clay coated muslin which show various Buddhist figures and scenes. There are generally two types: mandalas, which are a geometrical based design, often representing the layout of a temple and devoted to a deity; and figures, which show a Buddha, Tara, or other figure. I had taken a class on drawing/painting a mandala when I was in San Diego and became interested in this art form. For me, the style is reminiscent of the miniature painting of the Middle East and India. I'm also interested in the symbolism and the use of images in religion. When we decided to go to Nepal, I thought it would be a great opportunity to learn more about the painting techniques.

Thangkas in Kathmandu

Thamel, in Kathmandu, is full of thangka galleries and schools. I visited a few and talked to some of the artists. However, the most informative conversation I had with a thangka artist was in Bouddha where I met an artist/teacher named Tsonamgel Lama.

I told him I was interested in painting classes and instead of him leaping into a description of a course for foreigners as many other artists had, he said most Westerners weren't satisfied with the classes. “Even though they say, 'Yes, we are satisfied,' I know they aren't.” He explained the difficulty of teaching this art form to Westerners: the traditional way of learning thangka painting is apprenticeship which lasts 5-6 years. Westerners come in with a week to a month and want to learn everything and have a completed piece. He said Westerners expected to start with drawing and finish with painting and do it quickly.

The traditional training would start with the apprentice learning about the materials, where to gather them, how to make them, etc. He would learn painting techniques and spend time on each aspect-- for example clouds, shading the sky, shading hills, painting flowers in different stages of blooming. At this stage the apprentice might work on part of a professional artist's thangka.

The apprentice would learn painting techniques like pointalism, shading, and linework as well as painting lines in gold. The final step would be learning to draw the figures. This can take 6 months to one and a half years because one must learn all the proportions and positions. The apprenticeship is free and the students also receive room and board. However, the teacher has a contract with the student which states the teacher is able to sell the student's work to cover costs. After completion of the apprenticeship, the student will hopefully work in the shop.

After our discussion, Tsonamgel recommended that I should focus on painting techniques-- especially linework since that tended to be most difficult. He offered to help me find a teacher but in the end, I decided to study in Pokhara.

Painting a Thankga in Pokhara

After arriving in Pokhara, we decided we would spend a month there instead of Kathmandu. I quickly found a thangka teacher and after returning from Ghorepani, started class. My thangka teacher's name is Lawang. On first meeting, he seems like a hipster and you could mistake him for a Western obsessed Nepali with long hair, good English, and a carefree manner. However, after talking to him a bit I found he also has a wise and serious side. During the time I spent painting we had many informative and interesting conversations about thangkas and Buddhism.

The first step of painting a thangka is preparing the canvas. This involves stretching fabric on a frame then covering it with a mix of powdered white clay (caolin) with watery glue (made from yak skin) and leaving it to dry in the sun. After it is dry, a very light layer of glue and water is added to the canvas which is then polished with a rock.

Lawang's wife, Rupa, also works in the store. She paints Buddha eye designs and dragons which Lawang draws for her. She also helps customers. They have a daughter who is two and a half and loves trying to write. Lawang is from east of Kathmandu. His father wanted him to be a painter but he didn't want to. He tried a number of other jobs but none worked out so finally he decided to obey his father and paint.

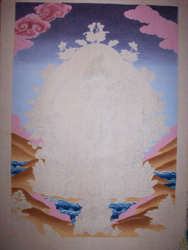

After the canvas was ready and I traced a White Tara on it, I started painting the sky. The sky is first painted with a light color in short vertical (slightly slanted) strokes. This seems to make the paint look more even. We painted using sable brushes and poster guache. Adding some glue prevents cracking with multiple layering.

Then a darker color is mixed very thin and painted on in small strokes-- darker at the top but with more water added so the shade becomes lighter going down. These strokes are horizontal, progressive layers of strokes are added always smaller and seeking to cover any spots of the lighter color. This takes a long time.

Thangkas in Kathmandu

Thamel, in Kathmandu, is full of thangka galleries and schools. I visited a few and talked to some of the artists. However, the most informative conversation I had with a thangka artist was in Bouddha where I met an artist/teacher named Tsonamgel Lama.

I told him I was interested in painting classes and instead of him leaping into a description of a course for foreigners as many other artists had, he said most Westerners weren't satisfied with the classes. “Even though they say, 'Yes, we are satisfied,' I know they aren't.” He explained the difficulty of teaching this art form to Westerners: the traditional way of learning thangka painting is apprenticeship which lasts 5-6 years. Westerners come in with a week to a month and want to learn everything and have a completed piece. He said Westerners expected to start with drawing and finish with painting and do it quickly.

The traditional training would start with the apprentice learning about the materials, where to gather them, how to make them, etc. He would learn painting techniques and spend time on each aspect-- for example clouds, shading the sky, shading hills, painting flowers in different stages of blooming. At this stage the apprentice might work on part of a professional artist's thangka.

The apprentice would learn painting techniques like pointalism, shading, and linework as well as painting lines in gold. The final step would be learning to draw the figures. This can take 6 months to one and a half years because one must learn all the proportions and positions. The apprenticeship is free and the students also receive room and board. However, the teacher has a contract with the student which states the teacher is able to sell the student's work to cover costs. After completion of the apprenticeship, the student will hopefully work in the shop.

After our discussion, Tsonamgel recommended that I should focus on painting techniques-- especially linework since that tended to be most difficult. He offered to help me find a teacher but in the end, I decided to study in Pokhara.

Painting a Thankga in Pokhara

After arriving in Pokhara, we decided we would spend a month there instead of Kathmandu. I quickly found a thangka teacher and after returning from Ghorepani, started class. My thangka teacher's name is Lawang. On first meeting, he seems like a hipster and you could mistake him for a Western obsessed Nepali with long hair, good English, and a carefree manner. However, after talking to him a bit I found he also has a wise and serious side. During the time I spent painting we had many informative and interesting conversations about thangkas and Buddhism.

The first step of painting a thangka is preparing the canvas. This involves stretching fabric on a frame then covering it with a mix of powdered white clay (caolin) with watery glue (made from yak skin) and leaving it to dry in the sun. After it is dry, a very light layer of glue and water is added to the canvas which is then polished with a rock.

Lawang's wife, Rupa, also works in the store. She paints Buddha eye designs and dragons which Lawang draws for her. She also helps customers. They have a daughter who is two and a half and loves trying to write. Lawang is from east of Kathmandu. His father wanted him to be a painter but he didn't want to. He tried a number of other jobs but none worked out so finally he decided to obey his father and paint.

After the canvas was ready and I traced a White Tara on it, I started painting the sky. The sky is first painted with a light color in short vertical (slightly slanted) strokes. This seems to make the paint look more even. We painted using sable brushes and poster guache. Adding some glue prevents cracking with multiple layering.

Then a darker color is mixed very thin and painted on in small strokes-- darker at the top but with more water added so the shade becomes lighter going down. These strokes are horizontal, progressive layers of strokes are added always smaller and seeking to cover any spots of the lighter color. This takes a long time.

I kind of imagined thangka painting as the activity of monks. I had an image of studying in a monastery. In fact, I think most thangka painters probably don't treat it as a sacred activity but rather a career. Working in a gallery in Lakeside is definitely not a monastic type of existence. In fact, I'm finding that you really don't have to be a hermit to do art. Being in the shop painting is kind of social. Though usually I paint silently there are plenty of welcome distractions. Sometimes people walk in and chat, Sria (Lawang and Rupa's daughter) will come in and say something in Nepali to me, try to find a pencil in my bag to write with, or we'll play a little.

The other day a guy from Japan, Hiro, whose girlfriend is studying thangka, chatted a bit. Dipak stopped by one day and said “Hi”. Sidhu, who owns the shop next door and who has become friends with Rowshan (they play music together) sometimes stops by. Rupa sits on the front steps singing and playing a drum from Sidhu's shop, playing with Sria. Her friends sit and joke. Occasionally they try to get customers into the shop, “Come in, please.” “I have more mandalas inside”.

From the inside of the shops I see how long it takes to make a painting and how few customers come in. Somehow they manage. It is low season so things are pretty dead. High season is a lot better. It took me a week to paint sky, hills and most of the water. It's repetitive work but there is something relaxing about it and I like seeing the quality, texture and color change as I work.

One day I asked Lawang if, since his last name is Lama, he had an ancestor who was a priest. He said his grandfather was a priest as well as his father. His father had been encouraging him to learn priest work because when he died, the people who went to him would turn to his son. Lawang was not too thrilled about the prospect. He said it was late for him to learn everything-- casting horoscopes, predicting fortuitous times for marriage, etc. He said, with relief, he probably wont have to since his brother was studying in a monastery.

He also said it used to be that priests would paint thangkas ( “than” means canvas and “ku” means “god”) often when someone died because it was considered pleasing to the gods. I guess it is written in the Tibetan book of the dead. They would also be painted if someone was sick. However, now they were more fashionable as art. I asked if people ever asked things like, “My son is taking a university entrance exam, can you paint a thangka to help him pass?” He laughed and said, “We just say, he must work hard and then he will pass.”

He said now priests might order a thangka from a painter and tell the painter which figures to paint and where instead of painting it himself. Colors on religious thangkas are set using straight pigments and not mixed as they are now.

Lawang gave me a description of the wheel of life. In Om mani padmi hung, each syllable stands for a station of the wheel. Each section has its problems. The goal is to break free of the wheel and achieve Nirvana.

The sections included human life, ghosts, animals, demons, heaven, and one more place. I was interested to see that heaven was also considered some place that was not positive. Lawang explained that in heaven, the occupants suffered from pride thinking, “I'm in Heaven so I'm really great” which ruined their karma and sent them lower. Animals suffered from ignorance, demons from envy which kept them eternally fighting, ghosts suffered from greed and were always hungry with big bellies but couldn't eat. The best place to be on the wheel, was the human world because only the humans were able to break free.

From the inside of the shops I see how long it takes to make a painting and how few customers come in. Somehow they manage. It is low season so things are pretty dead. High season is a lot better. It took me a week to paint sky, hills and most of the water. It's repetitive work but there is something relaxing about it and I like seeing the quality, texture and color change as I work.

One day I asked Lawang if, since his last name is Lama, he had an ancestor who was a priest. He said his grandfather was a priest as well as his father. His father had been encouraging him to learn priest work because when he died, the people who went to him would turn to his son. Lawang was not too thrilled about the prospect. He said it was late for him to learn everything-- casting horoscopes, predicting fortuitous times for marriage, etc. He said, with relief, he probably wont have to since his brother was studying in a monastery.

He also said it used to be that priests would paint thangkas ( “than” means canvas and “ku” means “god”) often when someone died because it was considered pleasing to the gods. I guess it is written in the Tibetan book of the dead. They would also be painted if someone was sick. However, now they were more fashionable as art. I asked if people ever asked things like, “My son is taking a university entrance exam, can you paint a thangka to help him pass?” He laughed and said, “We just say, he must work hard and then he will pass.”

He said now priests might order a thangka from a painter and tell the painter which figures to paint and where instead of painting it himself. Colors on religious thangkas are set using straight pigments and not mixed as they are now.

Lawang gave me a description of the wheel of life. In Om mani padmi hung, each syllable stands for a station of the wheel. Each section has its problems. The goal is to break free of the wheel and achieve Nirvana.

The sections included human life, ghosts, animals, demons, heaven, and one more place. I was interested to see that heaven was also considered some place that was not positive. Lawang explained that in heaven, the occupants suffered from pride thinking, “I'm in Heaven so I'm really great” which ruined their karma and sent them lower. Animals suffered from ignorance, demons from envy which kept them eternally fighting, ghosts suffered from greed and were always hungry with big bellies but couldn't eat. The best place to be on the wheel, was the human world because only the humans were able to break free.

Another day, Lawang mentioned that Buddhism had its roots in the Bon religion-- a very ancient Tibetan religion. This is where the use of thangkas come from. The Bon religion is an animistic religion so the use of images is an important part of it. The Thamang people in Nepal still practice it. They were originally from Tibet but came to Nepal as fighters for a Nepalese king and were invited to stay. Many thangka painters are from the Thamang ethnic group.

The same day, a guy from Australia stopped by. He was in Nepal studying thangkas and was particularly interested in the ancient Bon ones found in old monasteries and temples. He also mentioned the Bons utilized hallucinogenic plants (mushrooms). I wonder if the Bon religion is related to the shamanic practices of the native people of Siberia. It is also an animistic religion. Later I read Buddha, himself, shunned the worship of idols and images but later they were pulled back into the religion from Bon and Hindu practices.

It took me a month to finish painting my thangka. The hardest part for me was, as Tsonamgel predicted, was the linework. But, this is something that will come with practice I guess.

The same day, a guy from Australia stopped by. He was in Nepal studying thangkas and was particularly interested in the ancient Bon ones found in old monasteries and temples. He also mentioned the Bons utilized hallucinogenic plants (mushrooms). I wonder if the Bon religion is related to the shamanic practices of the native people of Siberia. It is also an animistic religion. Later I read Buddha, himself, shunned the worship of idols and images but later they were pulled back into the religion from Bon and Hindu practices.

It took me a month to finish painting my thangka. The hardest part for me was, as Tsonamgel predicted, was the linework. But, this is something that will come with practice I guess.

[ View 1 Comments

|

]

Comments

Lama Tsonamgel -

posted on 4/30/2009

I am glad that you have learnt to paint thangka painting in Pokhara. I wish you all the best. Keep it up!!

- Lama Tsonamgel

Tushita Heaven Thangkas

KTM-6, Bouddhanath, Kathmandu, Nepal

www.thangkatushita.com

- Lama Tsonamgel

Tushita Heaven Thangkas

KTM-6, Bouddhanath, Kathmandu, Nepal

www.thangkatushita.com

Powered by My Blog 1.69. Copyright 2003-2006 FuzzyMonkey.net.

Created by the scripting wizards at FuzzyMonkey.net..

(Code modified by Rowshan Dowlatabadi)

Created by the scripting wizards at FuzzyMonkey.net..

(Code modified by Rowshan Dowlatabadi)